Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Jal Jeevan Mission: Some Gaps in its Implementation in Jharkhand

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

31 July, 2025

Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) is a flagship program launched by the Government of India in 2019 with the vision of ensuring regular drinking water supply in every rural household through a ‘functional household tap connection’ (FHTC). Even public institutions at the grassroots, such as schools, childcare centres (Anganwadi), and health centres are to be covered under this program. The functionality primarily refers to a minimum service level of 55 liters per capita per day (lpcd) of water of prescribed quality as defined by BIS:10500 standard ('Bureau of Indian Standards – Drinking Water Specification') to be supplied on a regular basis. An overview of how JJM is being implemented in the state of Jharkhand, where many villages and hamlets are remotely placed and inhabited by disadvantaged tribal populations, was presented in the preceding publication titled “Jal Jeevan Mission: Action for its Implementation in Jharkhand”. At the core of the program in Jharkhand lie two types of water supply schemes, namely, the single village schemes (SVS) sourced from the local aquifers in groundwater-rich areas, and the multi-village schemes (MVS) based on surface water in locations where groundwater is inadequate or quality-affected. JJM has enabled an increase in rural FHTC coverage in Jharkhand from a mere 5.52% at the start of the program in April 2019 to 55.03% in June 2025. A sample survey to assess the functionality of the FHTCs, as proposed within the framework of the JJM Guidelines from Government of India, was undertaken in Jharkhand in 2022. The sample assessed comprised 4575 households having working tap connections in 370 villages situated across all the 24 districts of the state. The report of this functionality assessment noted that only 55% of these sampled households in the state had ‘fully functional’ FHTCs, lying at the intersection of all the 3 criteria - Adequate Quantity (>=55 lpcd), Fully Regular Supply (every day or as decided at the community level) and Potable (Quality as per the BIS:10500 standard). This adversely implies that the remaining 45% FHTCs in the sample fail to be ‘fully functional’. This gap is indicative of issues concerning the efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of JJM schemes which are already implemented. However, an analysis of the reasons underlying such a situation has not been attempted in the functionality assessment. To assess the status of JJM implementation in Jharkhand beyond mere figures, and to contribute to improving its efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability, a field-based qualitative study was undertaken by the authors in March 2025. A total of 28 villages in four districts, namely, Seraikela-Kharsawan, Khunti, Gumla and Latehar, were visited where 34 SVS and 5 MVS were examined. Village and scheme selection were guided by a comprehensive set of criteria. The population composition criterion ensured representation across mixed communities (tribal and non-tribal), tribal-majority villages, and hamlets inhabited by Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs). The remoteness of habitation criterion allowed the inclusion of both well-connected villages with good road access as well as more isolated hamlets with poor or no road connectivity. The location within the water supply scheme was also considered, incorporating habitations situated at the head, middle, and tail ends of the distribution network. Finally, pre-identified implementation gaps—such as low groundwater levels and topographic hinders— were also considered in order to enable deeper analysis. Qualitative insights into the JJM schemes and their operational issues were gathered through field observations and semi-structured interviews with beneficiary households, staff of the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (DWSD) which is the nodal agency, and local staff responsible for the O&M of the schemes. The findings of the study are presented on the Millennium Water Story in a series of photo articles. In general, the study showed that the SVSs and MVSs under JJM have widely facilitated the access of rural households to piped water supply within premises through FHTCs, but there exist important questions of concern. The functioning of many of the schemes, and hence the functionality of the FHTCs served by these, is not up to the mark, thwarted by a diversity of factors. This second article in the series aims to present the findings regarding the status of functionality of the implemented single- and multi-village schemes under JJM in Jharkhand and analyze the factors that affect their performance. It was interesting to note that out of the 28 villages included in the study sample, nine are officially ‘certified’ as having achieved ‘Har Ghar Jal’ (HGJ) status, while two more villages have been ‘reported’ as fit for HGJ status. This certification or reporting indicates that all households in these villages have access to an FHTC. While ‘reporting’ is the first step taken by the DWSD, ‘certification’ is the second and final step, occurring when the village assembly (Gram Sabha) passes a resolution to this effect. However, it was found that many of these HGJ-certified or reported villages have problems regarding access to FHTCs or their functionality. The common issues identified in the study include broken, leaking or missing taps; damaged or leaking pipes; low water pressure in pipelines; substandard quality of work; missing or non-functioning components; inadequate and intermittently functioning schemes; inoperative SVSs; and excluded households. Also, the Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) component of the program is very weak. The photographs presented in this article have been purposefully selected as the best visual illustration of the commonly observed problems mentioned above. These photographs serve as representative examples and should not be interpreted as depicting problems exclusive to the specific districts named. Rather, they denote broader issues found across the various districts included in the study, except in cases where specific exceptions are explicitly mentioned. The title photo depicts a broken tap at the head of a broken FHTC pipe within the premises of a beneficiary Anganwadi centre in the Khunti district. Villagers reported that the source-SVS for this FHTC stopped supplying water just a few weeks after it became operational in 2023, and eventually, the tap’s cartridge and handle also detached. Despite promises made, the contractor responsible for the construction and O&M of the SVS did not take any action. This situation reflects poorly on both the quality of the work and the accountability of those involved.

The remains of a broken plastic tap at a recently installed FHTC in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

According to guidelines for implementing JJM in Jharkhand, each FHTC is supposed to be fitted with durable and quality material as a brass tap. However, during the study, many locations were found with plastic taps, regardless of whether they were part of the SVS or MVS networks. Plastic taps are particularly susceptible to damage, especially when installed outdoors in open courtyards, which is often the case. When a tap is damaged, it can lead to two major issues: if the tap is permanently closed, the water supply to the household is disrupted; if the tap is left open when broken, it can cause significant water wastage during supply hours. In the first scenario, the beneficiary household faces restricted water access, while in the second scenario, households at the end of the network may experience low pressure or a complete lack of water in the pipeline. It is unclear who should be responsible for replacing the broken taps. Contractors are often reluctant to take on this responsibility, and beneficiary households lack the motivation to address the issue due to lack of ownership and their insufficient awareness of their own role in the program.

Valuable clean drinking water gushing out of a ‘tap-less’ FHTC in a rural household in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

Another problem observed in the villages was that of ‘tap-less’ FHTCs. In one case (shown in the photo above), the study team was informed that no tap had been installed from the start of the scheme. In some other cases, FHTCs have become ‘tap-less’ after a broken tap has been removed. In either case, while water can still be collected directly from the pipe, it often brings serious consequences for the rest of the distribution network. Unrestricted flow at the beginning of a line can leave tailenders without any water. Over time, this kind of wastage can also threaten the sustainability of the water source, which is a significant concern.

A leaking FHTC that blatantly wastes valuable water resources during the supply hours in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

Leaking taps are another widespread issue observed in many JJM schemes, with serious implications for the overall distribution network. Leakage at the beginning of the pipeline can deprive tail-end households of their supply. It also leads to water wastage, though the impact may be somewhat less compared to that from broken or missing taps. Responsibilities for fixing leakages in the individual FHTCs are again fuzzy, and the beneficiary households generally tend to believe that the agency should act. Handing over schemes to the communities is an integral aspect of the scheme. However standard operating procedure for the same, which could have clearly distributed the responsibilities between the agency and the community, is lacking in the program.

Exposed Ductile Iron (DI) pipes bringing water from a newly installed MVS in Khunti district

A vital component of the piped water supply system is the pipe and different kinds of pipe, such as Ductile Iron (DI), high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) pipes of diverse diameters are commonly used in the SVS and MVS schemes. A ground rule in laying down a piped water network is to place pipes carrying water to or from a source at a minimum depth of one meter below the soil. This helps reduce external impact, thereby minimizing the risk of damage. But it was observed that the pipe depth is generally shallower. To make things worse, at several places, the pipes were found to lie exposed to the ground. This makes the piped infrastructure extremely vulnerable to damage from transport infrastructure or other overground impacts, leading to leakages and water supply disruptions.

Exposed PVC pipes conveying water from DI pipe to FHTCs in a village in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

At some of the places, a reason cited as responsible for pipes exposed to the ground was stopping of the work midway by the agencies due to lack of funds. Another reason, perhaps more important, has been the lack of effective mechanisms for quality control of the implementation from the start. The engagement of Third-Party Inspectors to ensure quality, as per the JJM implementation guidelines, has started at a very late stage in the state.

Leakage from an MVS-fed supply pipeline along a village street in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

Water leakage from JJM scheme pipelines along village streets is not an uncommon sight, often a result of shallow underground placement of pipes or poor work quality. The villagers mentioned that the leakage shown in the above photo began about a week before the study visit was made. However, they were unable to lodge a complaint and get the repair done because of lack of information about the agency responsible for this purpose. As a result of the leakage, the water pressure in the pipes remains low, and households at the tail-end of the distribution network end up receiving a trickle.

Water supply received at extremely low pressure in a rural household tap in Khunti district

Low water pressure in the FHTC was a common complaint that has roots in several problems. Broken, leaking or missing taps as well as pipeline leakages as causes have been already illustrated. Another significant cause is the undulating topography of the region, which has not always been prudently factored into the distribution network design. Standard designs for the schemes have been prepared at the state headquarters, and their modification as per the ground situation is not done. This often results in low water pressure—or even dry taps—in parts of the habitation located at higher elevations. This can be true of SVS as well as MVS networks.

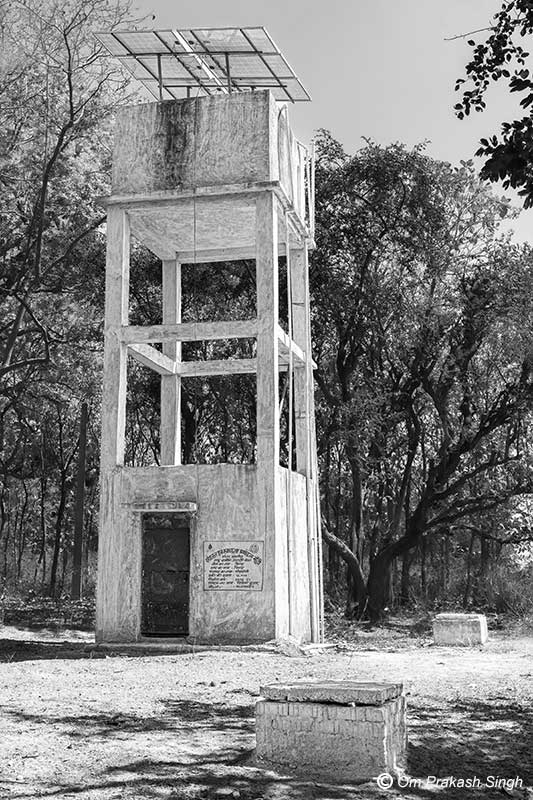

A non-functional SVS in a ‘Har Ghar Jal’ village in Khunti district

In many of the SVSs examined in this study, functionality was reported as a problem because the source tubewell has turned dry after installation. Consequently, although these habitations are officially classified as ‘covered’ under JJM, their residents continue to lack access to functional and reliable water supply. The SVS shown in the above photo belongs to a HGJ certified village inhabited mainly by tribals. Contrary to what the certification states, the residents here reported that this SVS has operated for barely 1.5 months after its start around September 2024. Thereafter, for nearly 5 months (at the time of the study visit), the scheme has been dry. The submersible in the borewell at the SVS doesn’t discharge adequate water and consequently the overhead tank remains empty.

The handpump at the SVS shown above, producing scanty water in Khunti district

The borewell at the SVS shown in the preceding photo is also equipped with a handpump, but even its discharge is meagre. The beneficiary households are of the opinion that the groundwater available at the drilled depth is insufficient for abstraction. This situation is similarly observed in some of the other SVS borewells in this HGJ village, but no remedial action has been planned yet. In fact, the topography of the state and the underlying stratigraphy play an important role in this context, which makes the sustainability of many water sources questionable. For example, water may exist in fissures, and their capacity is often limited. In such cases, traditional sources of water in the village might have served as useful alternatives, but these have not been integrated into the schemes.

An SVS rendered inoperative due to borewell collapse in a ‘Har Ghar Jal’ village in Latehar district

Another significant SVS-related issue is borewell collapse, which has been particularly observed in the districts of Gumla and Latehar. According to users of the SVS shown in the above photo, which is in a HGJ certified village, the system has been non-functional for the past one year due to this reason. Local staff from the DWSD explain that this typically occurs because of swampy soil conditions occurring at a depth beyond 100 feet. This again raises concerns about the quality and seriousness of the work, since the system should have been designed and built with due consideration of the local stratigraphic conditions. Appropriate precautions should have been incorporated to prevent potential structural failures. But the use of standardized scheme designs prepared at the state headquarters have precluded their modification as per the grounded exigencies.

Close-up of the collapsed borewell in Latehar district (seen in the preceding photo)

Though one year has passed, the beneficiaries of this SVS haven’t heard anything from the contractor yet regarding action for reinstating the borewell and restarting the SVS. Delays in repairs and replacements are often common. In cases of serious system flaws or breakdowns like this one, these delays can be prolonged.

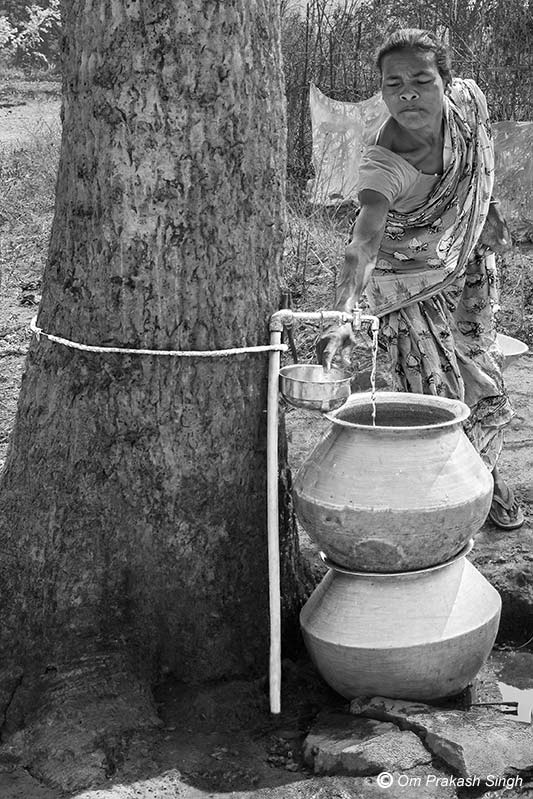

Fetching water from a ‘makeshift’ FHTC outside the house in a village in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

To provide a sustainable water supply at the household scale, an FHTC - the core of JJM - should comprise a single tap mounted on an RCC pillar, together with a concrete base to manage drainage. However, some contractors have taken the liberty to redefine FHTC as a blue PVC pipe near a household at the end of which a tap is attached for withdrawing water. The habitation depicted in the photo is served by an MVS-based piped water distribution network, but every household has an FHTC that is either similar to or even worse than the one shown above. Notably, the pipe seen tied to a tree was secured by the beneficiary household itself. Many residents are forced to collect water from PVC pipes lying on the ground, which lack taps altogether. Villagers here reported that taps were initially installed by the contractor, but due to the absence of proper pillar support, they broke within a short time. As a result, water now flows freely from open pipe-ends during supply hours, which significantly reduces pressure in the pipeline and thwarts water distribution down the network.

A 12000-liter capacity SVS lying idle in a ‘Har Ghar Jal’ village in Khunti district due to non-functioning dual motors

The quality of the machinery installed is yet another important concern. For running a 12000- or 16000-liter capacity SVS, dual motors are provided. Beneficiaries of a number of such large-sized systems having two motors reported that one of these is often non-functional from the start. In the HGJ village in Khunti district (depicted in the above photo), there exist several large-sized SVS schemes. However, out of the 5 SVSs visited here that possessed dual motors, 3 were reported to have one of the motors as non-functioning. As a result, when the operational motor gets out of order, the tank fails to fill up, and the beneficiaries must go without water. In all cases, though the beneficiaries have reported the matter, they do not know whether the non-functioning motor will ever be repaired or replaced.

An inoperative MVS in Gumla district because of disrupted power supply

MVS too present important gaps in their operation. Several hours of uninterrupted power supply is essential for running all the functions in these rather large infrastructures. The main power-dependent functions range from raw water abstraction from the river, through the multi-step water treatment plant (WTP) processes, right up to filling up the elevated service reservoirs (ESRs) that finally supply treated water through the FHTCs. It is mainly the piped water distribution network after the ESR that is gravity-based. However, the power supply in rural areas can be unreliable. As a result, MVSs may remain inoperative for days. The MVS depicted in the above photo, which supplies drinking water to 1371 households in 6 villages, faces undeclared power interruptions at least 5-6 times every month, each lasting 1-2 days. This accounts for 5-10 days of water supply disruption per month, which is not trivial. At the time of the field visit when this picture was shot, the WTP had been inoperative for the second day in a row.

The flocculation tank at the WTP of an MVS in Khunti district that misses vital raw water processing steps

The operation of water treatment plants raises concerns about water purification completeness in the MVS implementation. At the WTP shown in the photo above, the essential step of flocculation by mixing alum and lime solution with raw water has been skipped. Flocculation is the first essential step for removing particulate impurities through their aggregation into larger, heavier flocs that are later removed through sedimentation or filtration. While a flocculation tank and the structural facility for adding alum and lime solution to raw water do exist at this WTP, the effort to add alum and lime solution is not being made by the plant operator. Even worse is that there is no infrastructure for chlorination of the treated water before supply here. Both these omissions are made on the pretext that the MVS is still on ‘test-run’ and the quality of raw water obtained from the river is ‘very clean’.

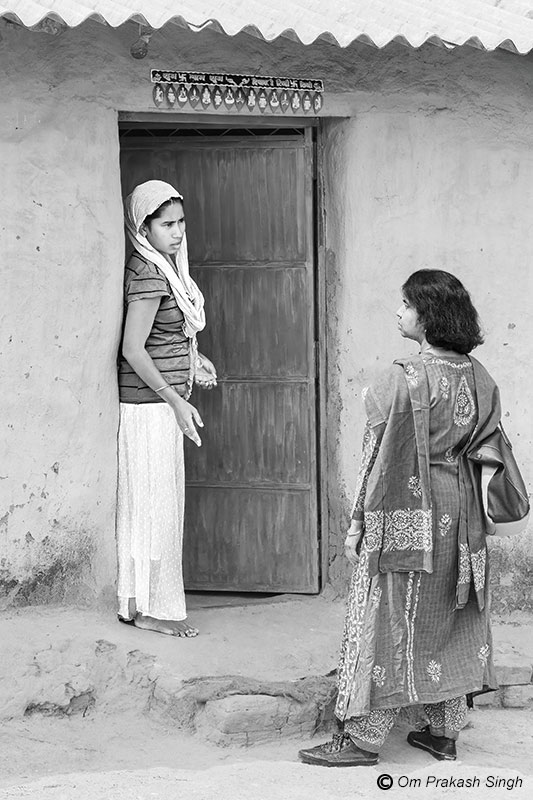

Interacting with a member of a household excluded from an MVS network in Gumla district

Excluded households is an important crosscutting issue that runs through SVS and MVS networks alike. At many places one or more households, or even clusters of households were found to have been left out of piped water networks. The contractors’ versions generally attribute the exclusion to the absence of household members from the village at the time of scheme implementation, or a coverage based on standardized census-based estimates rather than grounded village survey which would include all the households. Another reason often cited is the distant location of the household from the main supply pipe or the existence of a physical barrier such as national highway or railway track which can be surmounted only through formal inter-departmental permission. It is a pity that many such villages are reckoned as ‘fully covered’, or ‘Har Ghar Jal’, despite missing households that will perhaps never get coverage.

Inhabitants of an isolated hamlet belonging to a PVTG in Gumla district which lies uncovered due to lack of road connectivity

The above photo depicts the case of an isolated hamlet belonging to a PVTG in Gumla district. The hamlet is isolated, nestled amidst forests on a hilltop, without any road connectivity. This hamlet was covered with piped water supply in 2017-18 through a hand-dug well with community standpost. This well-based supply was later retrofitted as an SVS by installing an FHTC-based piped water network. However, the well is said to have collapsed some months ago due to vibrations of the motor. Consequently, the SVS today is inoperative and the PVTG households once again lack access to sufficient safe drinking water. Due to the absence of road access, the drilling equipment cannot be brought into the village to install a borewell.

Overflowing SVS tank due to inoperative sensor in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

An extremely common sight is that of overflowing SVS tanks. These tanks are supposed to have been fitted with sensors that should automatically switch off the motor when the tank is full. However, in many cases, the sensor is stated to be out-of-order. Another interesting narrative (put forward by the contractors) explains that in many schemes, the beneficiaries insist that they would like to have a continuous water supply throughout the day and hence the motor should not switch off. As a result, the sensors are forced to be turned off or taken away. Whatever the reason, the implication for sustainability of the groundwater source is immense, as the precious overflowing water lowers the water table and hence negatively impacts the sustainability of the SVS itself.

Substandard quality of RCC work at the base of an SVS in Khunti district

Poor quality of construction was another recurrent observation made during the study. At several places, though newly constructed, the concrete work already shows signs of damage. This puts the erected infrastructure such as tanks at risk of collapse. The status of pipes and FHTCs has already been mentioned earlier. At one place, a solar panel was reported to have flown away in a storm.

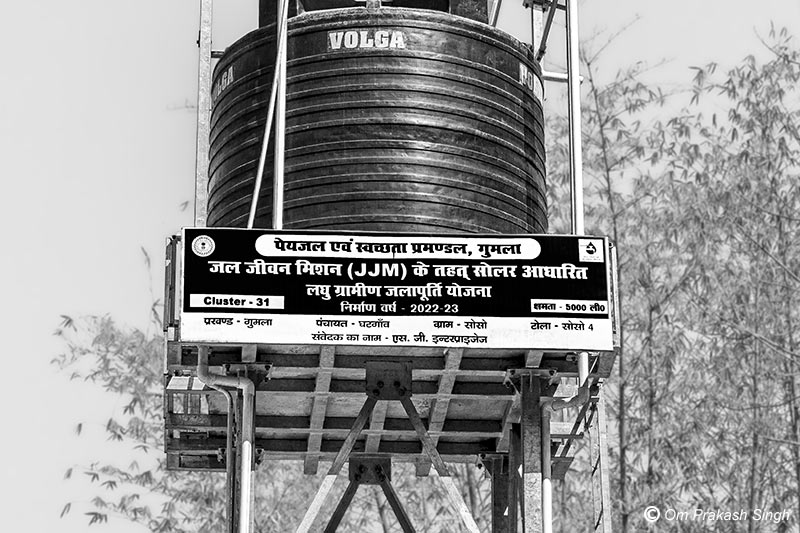

Lack of contact information on an SVS sign board in Gumla district

SVS as well as MVS-based piped water supply networks are complex systems that are prone to breakdowns and damage at times. Also, their complexity requires trained personnel to fix the problems. In order to ensure speedy repair, the program guidelines require a sign board to be erected at a conspicuous location giving not only relevant details of the scheme (such as commencement and completion dates and total cost), but also the contractor’s name and the contact details of those who can help with carrying out repairs when needed. The latter include the Executive or Junior Engineer of DWSD, and that of the village water committee (Paani Samiti) Chairperson and Secretary of the village government (Gram Panchayat). Contact details as above were found to be completely missing at the JJM schemes in Gumla district (as seen above), and incomplete or outdated at some other sites of study.

An untrained Jal Sahiya who fails to contribute to water quality monitoring in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

Water quality monitoring and surveillance (WQMS) is a central component in JJM and the grassroots functionary responsible for the task at the village scale is the Jal Sahiya in Jharkhand. Jal Sahiyas are supposed to be trained to carry out water quality tests using field-test kits distributed by the department. However, not all Jal Sahiyas have received training, and one such untrained functionary is seen in the photo above. She is, nevertheless, mandated to submit water quality reports on a regular basis. The functioning of JJM-associated laboratories is perhaps no better. In one instance, a water sample sent for testing at the district laboratory during the study visit failed to examine the level of certain essential contaminants. This not only exposes the weaknesses of WQMS, but in turn also questions the quality of the water supplied through JJM schemes.

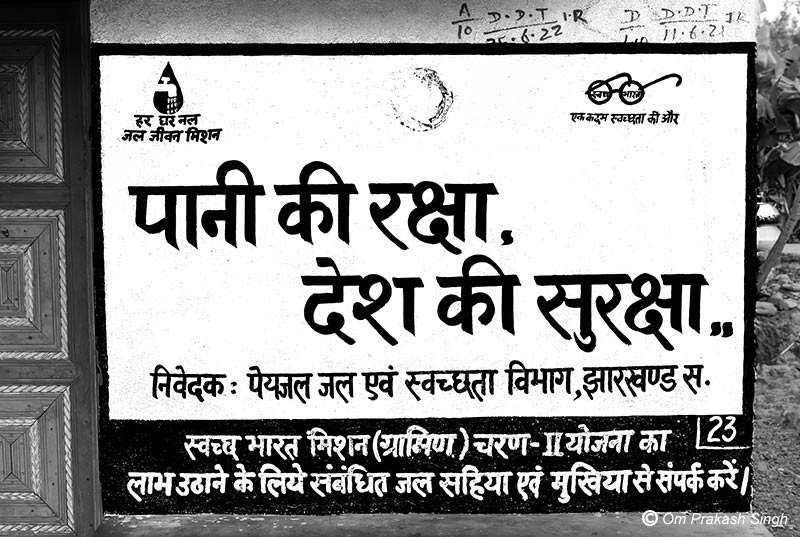

One of the rare IEC slogans of Jharkhand that promotes water conservation in Khunti district

JJM is not just about creating water infrastructure but also its long-term sustainability which, in turn, rests on the capacities of local communities to own, manage, operate and maintain their in-village water supply systems. Towards this end, an IEC component has been specifically highlighted in the JJM guidelines with the aim of creating awareness and driving positive behavioral changes in local user communities. IEC should concern aspects such as prevention of wastage and misuse of water, conservation of water resources, and affirmative action for protection of drinking water sources. Slogan writing on public walls and community spaces is one of the recommended IEC interventions, but ironically, such slogans were found to exist in only two of the 28 villages visited in this study. One of these villages was in Seraikela-Kharsawan district, where a wall painting within school premises was seen. The second one was the historic village of the legendary tribal leader Birsa Munda in Khunti district, where several water conservation slogans were painted on the walls along the main village street when the Prime Minister was to make a visit in 2023.

The latest figures regarding FHTC coverage in the 4 districts included in this study present quite a positive scenario with 62.4% in Khunti, 67.7% in Gumla and 73.4% in Latehar. However, in Seraikela-Kharsawan, the coverage is comparatively low at 48.8%. The slow progress in coverage under JJM is undoubtedly a concern, but an even greater concern is the upkeep of the functionality of the schemes and their FHTCs already created under JJM. This photo article has focused on the second concern and some of the commonly observed deficiencies in this regard have been outlined. These deficiencies highlight the gaps between the program’s normative framework, as laid down by the government, and its actual execution on the ground. As is obvious from the situations illustrated above, these gaps thwart the functionality of the FHTCs provided in the rural settings in different ways. One of the objectives of the state-level report for functionality assessment of FHTCs was to “suggest measures for mid-course correction to improve the functionality of FHTCs”. However, the report failed to examine the factors which thwarted 45% of the FHTCs of the sample households to be ‘fully functional’, leaving this highly relevant objective incomplete.

The findings presented in this article fulfil this critical deficiency by highlighting the gaps in the implementation of JJM in Jharkhand. These deficiencies bring forth some important issues concerning the functionality of the FHTCs and the overall status of the program in the state. First is the issue of ‘Har Ghar Jal’ (i.e., water access in every household) versus ‘Har Ghar Nal’ (i.e., tap access in every household). What is assessed in JJM reporting is ostensibly HGJ, but in reality, it is ‘Har Ghar Nal’ (HGN) because monitoring the FHTC installation does not necessarily imply monitoring the water supply through the installed FHTC. Infrastructure installation cannot automatically guarantee service provision. A number of factors (as illustrated above) intervene between installation of the FHTC and a regular flow of adequate potable water in the tap. Second, even when a village is certified/reported as HGJ (irrespective of water availability in the tap), not every constituent household may necessarily have an FHTC. This study revealed that many households or habitations within the village end up being excluded. Third is the issue that even if the FHTCs get adequate water on a regular basis, the potability of the water cannot be ensured because the WQMS may not be up to the mark. The fourth issue is about the empowerment and engagement of the community, and the underlying IEC interventions for this purpose. The engagement of communities and the role of village governments (Gram Panchayats) to ensure sustainable use of water is crucial. These components have been unfortunately neglected, which has weighed heavily on effectiveness of the program, lack of ‘ownership’ by the community, and misuse and overuse of drinking water being important indicators.

Finally, the gaps in implementation highlighted in this article point to deeper, systemic deficiencies in the design of the JJM program. The ‘hardware’ issues such as broken, leaking or missing taps; pipe leakages; incomplete piped networks (leading to excluded households); faulty system design (e.g., distribution networks poorly adapted to the terrain); low water pressure or dry taps; substandard work (e.g., capsized bores, broken RCC platforms); defective SVS components; power failures; and weak WQMS are not isolated problems. These epitomize ‘symptoms’ which are caused by more deep-rooted ‘software’ issues like negligence regarding source sustainability; insufficiently trained staff; low staff motivation; lack of awareness among beneficiaries as well as their engagement; insufficient administrative regulation of private parties engaged in program implementation; inefficient grievance redressal system; poor inter-departmental coordination (e.g., for permits to lay pipes across highways or railway tracks); inadequate IEC and community mobilization; and lack of accountability. A number of these software issues are rooted in a deficient O&M framework in the program. The ambitious scheme for universal coverage of drinking water in Jharkhand has project costs calculated as per the Standard Operating Rates of the state, but no objective calculation for O&M costs of the schemes is available. The contribution of the Central Government to the construction of the schemes is provisioned but there is no financial roadmap for meeting their O&M costs.

The gaps highlighted in this article variously impact on the efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of service delivery under JJM, which ultimately thwart achievement of the program goals. An understanding of these gaps and their implications can provide valuable insights for improving the implementation of JJM in Jharkhand. The article emphasizes the importance of critically examining the implementation process to identify fundamental deficiencies, which can then be addressed appropriately. Without these corrections, existing gaps will persist, systematically undermining the program and hindering the goal of “leaving no one behind.” In villages where there are gaps in program implementation, women and children, who often manage the domestic water supply, face increased burdens. As a result, access to a sufficient, safe, and regular water supply for all household members is hindered. It is high time to initiate necessary action to improve the implementation of JJM, paving the way towards sustainable development and enjoyment of the human right to water and other concomitant rights.