Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Jal Jeevan Mission: Consequences of the Gaps in its Implementation in Jharkhand

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

29 August, 2025

The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), launched in 2019, aims to provide safe drinking water through functional household tap connections (FHTCs) in every rural home and public institution. Functionality of the FHTCs is defined using three criteria - Adequacy (>=55 liters per capita per day [lpcd]), Regularity (every day or as decided at the community level) and Potability (quality as per the BIS:10500 standard). A ‘fully functional’ tap lies at the intersection of the three. In Jharkhand, the FHTCs are supplied with water from either Single Village Schemes (SVS) using groundwater or Multi-Village Schemes (MVS) using surface water. A previous publication titled “Jal Jeevan Mission: Action for its Implementation in Jharkhand” outlined the program’s implementation process in the state. JJM has undoubtedly helped increase the number of rural household taps in Jharkhand from a mere 5.52% in April 2019 to 55.03% in June 2025. However, the implementation of the program in the villages reveals several gaps, which makes the functionality of these taps a great concern. Some of the program implementation gaps were outlined in the previous publication titled “Jal Jeevan Mission: Some Gaps in its Implementation in Jharkhand”. This was based on a field study conducted by the authors in March 2025, encompassing 39 Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) schemes across 28 villages situated in four districts: Seraikela-Kharsawan, Khunti, Gumla, and Latehar. While many of the sampled villages were not only ‘covered’ under JJM but also certified by the Panchayats (local village governments) as “Har Ghar Jal” (i.e., water access in every household), the mere presence of the water supply infrastructure did not ensure water access at home. This finding elaborates upon the outcomes of an earlier Sample Survey for assessment of the functionality of FHTCs undertaken in 2022 within the scope of the national JJM Guidelines. This assessment showed that as many as 45% of the FHTCs in the surveyed sample comprising 4575 households in the state were not ‘fully functional’. Even when the three ‘functionality’ criteria were considered individually, full attainment of the goal was missing, with ‘regularity’ being the weakest (70%). The qualitative findings of the authors’ field-based study (presented in the previous article) describe several underlying issues such as missing, broken or non-functional taps, low pressure in pipes, poor quality and functionality problems in the supply infrastructures, household exclusion weak communication and low community engagement efforts which ultimately thwart FHTC ‘functionality’ in different ways. This photo article takes a step further and examines the consequences resulting from the lack of functional FHTCs. A ‘fully functional’ FHTC would obviously mean that women and girls as domestic water managers, as well as other family members, would be able to undertake their various water-related chores at home. But if any one of the functionality criteria remains unmet, then water needs to be accessed from outside, which entails multiple challenges. Similar consequences face residents of those habitations where JJM schemes have been planned long ago but not yet completed. According to data from the Drinking Water and Sanitation Department (DWSD) in Jharkhand, the nodal agency responsible for JJM implementation, more than 42% SVS and 88% of MVS were in various stages of completion in June 2025. An additional study was carried out in four such villages in Khunti district which further helped understand the challenges faced by women and girls because of the absence of a water source at home. The photographs presented in this article are examples of the commonly observed consequences of a non-functional or missing FHTC, which cut across the different districts studied during the field visit. The title photo depicts the morning scene at a traditional water source in a village in Khunti district. Some women and a girl hurry home with pots of water collected from an old, dilapidated spring-based source, while others wash utensils at a nearby pond fed by another spring. These sources lie outside the village in lowland paddy fields with no proper access path, making water collection both difficult and unsafe because the area is muddy and slippery. Two SVSs are said to be under implementation in the village, but despite a June 2024 deadline for completion (shown on the government’s JJM information portal), work remains incomplete nine months later. Other community sources from earlier schemes are either non-functional or insufficient.

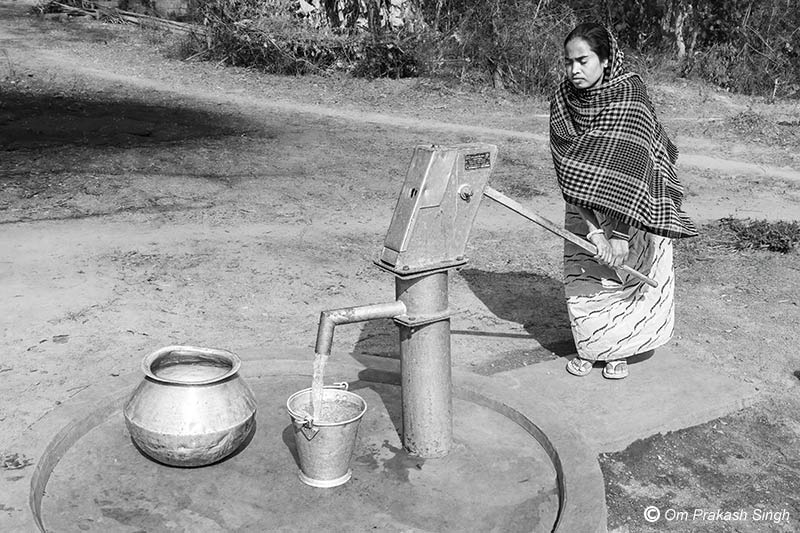

Collecting water from a community handpump in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

The photo shows a woman in a village served by an MVS whose supply presents problems of adequacy, regularity and quality. Frequent leakages disrupt regularity, and when functional, water is available for only 30 minutes in the morning—far from sufficient for household needs. Residents report unpleasant smells and tastes in the water, making it unsuitable for drinking or cooking, likely due to the treatment processes. As a result, the limited supply is primarily used for washing utensils, bathing, or watering animals. Drinking water is still sourced from an old well or the community handpump depicted in the photo. Insufficient IEC efforts have hindered behavioral changes necessary for adopting the water under JJM for drinking purposes. This issue is widespread, causing many women to rely on traditional water sources despite having household tap connections through JJM.

Procuring water from a damaged community well in Gumla district

This photo shows women taking water from a community well in a hamlet inhabited by members of a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Here all the criteria determining the ‘functionality’ of FHTCs at home are currently unmet. The SVS in this settlement became inoperative a few months ago due to collapse of the open well that served as its water source. As a result, women and girls are now compelled to rely on this well, which was originally developed as a drinking water source for the childcare center (Anganwadi) by deepening and lining a spring-fed traditional source. Unfortunately, after the implementation of the SVS in the hamlet, this well became neglected, leading to the deterioration of its walls. This condition makes pulling water from the well particularly dangerous, yet women have little choice but to do so.

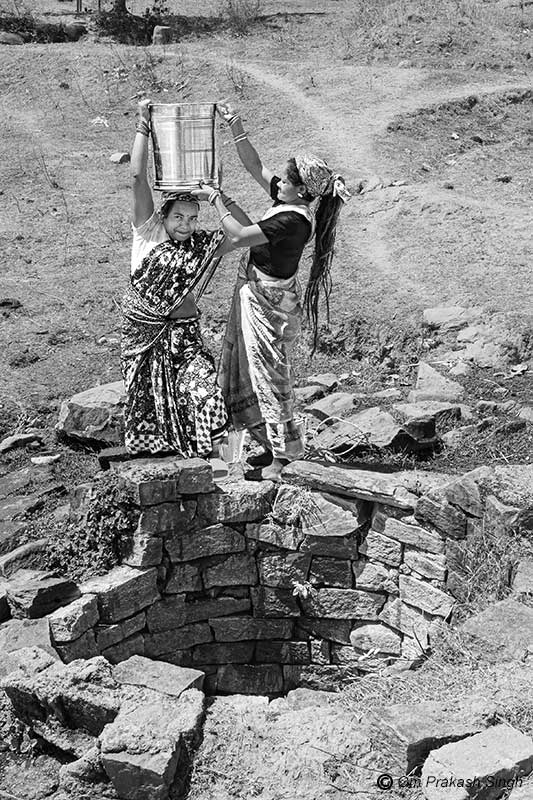

Struggling to balance a larger drum of water filled from the open well in Gumla district shown earlier

Fetching water from a public source often presents numerous challenges. For instance, this community well is located far from homes, requiring residents to make a lengthy walk multiple times a day to collect enough water for their domestic needs. To minimize the number of trips, women may choose to carry water in larger containers. In the accompanying photo, a woman is preparing to transport a large drum of water. However, balancing this heavy load on her head while navigating the winding, uneven village paths poses a significant challenge. This situation can have far-reaching implications for women’s health and well-being.

Preparing to collect drinking water from a spring-based traditional source located amidst distant paddy fields in Khunti district

When JJM infrastructure fails to provide adequate, regular or good-quality piped water as per women’s aspirations, in many cases they return to their traditional water sources which are often seen as more reliable. These are mainly spring-based sources located far from homes amidst lowland paddy fields. The access to such sources is often poor, and fetching water from these involves long, risky journeys with heavy loads, posing physical strain as well as risks of injury. The above photo depicts such a stone-lined spring-based traditional source (locally called ‘Paata Daarhi’) which is used by women from two neighboring villages. Both these villages are officially included in an MVS piped water network, but the supply is irregular, and the timing is also said to be inappropriate by women. Further, several households in both villages are yet to be fitted with FHTCs. Consequently, women living closer to this source depend on it for their daily water needs.

Forced to fetch drinking water from a distant traditional source in a ‘Har Ghar Jal’ village in Khunti district

The above photo depicts the situation in a large tribal majority village which is officially reckoned as ‘Har Ghar Jal’ (i.e., water access in every household) ‘covered’ by nine SVSs. However, three out of the five SVSs visited during the field study here were reported to have become inoperative soon after installation. As a result, women are forced to find alternative sources for fulfilling their water needs. The photo shows a traditional spring-based source (Paata Daarhi) located in the paddy fields. Women here undergo considerable hardships not only because of the distance and location in the agricultural fields, but also that it dries up during the summer months.

Procuring water from a traditional spring-based source in a PVTG village in Gumla district

While some of the traditional spring-based water sources are large, others are smaller in size. The photo above depicts a young lady fetching water from a small stone-lined traditional source (locally called Daarhi) because the SVS in her hamlet is non-functional. In the absence of piped water supply from the JJM tap, this source is seen as reliable in terms of availability as well as quality. However, its location down in the agricultural fields makes water procurement challenging.

Drinking water procurement from a traditional spring-based wooden-lined source in Khunti district

The traditional spring-based water sources in the Jharkhand villages are varied, differing in size, construction and capacities. However, one commonality is their distant location which makes drinking water procurement difficult, time-consuming and sometimes risky, as mentioned earlier. In the case shown in the photo, the underground spring has been developed as a drinking water source by fixing a tree trunk hollow instead of lining with stones. Such a source is locally called Kukuru Daarhi. According to users of the source, this water is more reliable in terms of taste, smell and availability, and hence continue to use it, though FHTCs are installed in more than half of the village households.

Procuring drinking water from an old damaged Kukuru Daarhi in Khunti district

The traditional water sources in the villages of Jharkhand are often several generations old. However, due to a lack of proper upkeep and maintenance, many of these sources are becoming damaged and degraded. In the case of Kukuru Daarhi, wood has a limited life span, and the photo shows one such source where the wooden lining is getting decomposed. Nevertheless, because of the slow pace of implementation of the two planned SVSs in the village, and absence of more reliable alternatives, women and girls from approximately 80 out of 110 households continue to rely on this deteriorating source for their water needs.

Heading home with headloads of drinking water from a distant traditional spring-based source in Khunti district

Rural women and girls as domestic water managers must ensure that enough is stored to meet the daily water needs. When a JJM scheme is non-functional or absent, water procurement from outside is obviously a necessity, but even when these function, the situation may not be significantly different. The limited and time-bound supply from JJM schemes poses challenges because it is often not feasible for the entire household to complete all their water-related chores during the brief period of supply. To cope, families must store water, but many tribal and other marginalized households lack facilities for water storage. This makes women and girls from poorer households access their traditional or other community water sources multiple times a day, traversing long distances with heavy loads of water.

Hauling drinking water from a distant source across a forested path in Khunti district

A young girl procuring water from a Paata Daarhi situated in paddy fields in Khunti district

Cleaning utensils at a spring-fed water source (Kukuru Daarhi) in Khunti district

Traditional water sources are used not only for drinking but also for household chores, with women and girls often visiting them twice daily — in the morning and late afternoon. Carrying and cleaning utensils on-site is physically demanding, time-consuming, and interferes with other essential activities. For girls, morning trips can cause them to miss school, while afternoon visits cut into their playtime. These tasks also pose health risks for young children. However, when FHTCs do not meet functionality standards or JJM schemes are delayed, households have few alternatives.

Girls hauling drinking water from a distant traditional source in Khunti district

In many households, when a functional FHTC is absent, girls are often tasked with fetching water while mothers manage other domestic chores. This can happen multiple times a day. The spring-based sources, though preferred for their taste and reliability, are usually far from home and lack proper paths. Girls must carry heavy water pots across uneven, narrow, and sometimes slippery field bunds. This not only consumes time meant for school or play but also poses risks of physical strain and injury.

Children returning home from a traditional spring source with headloads of water and cleaned utensils across agricultural fields in Khunti district

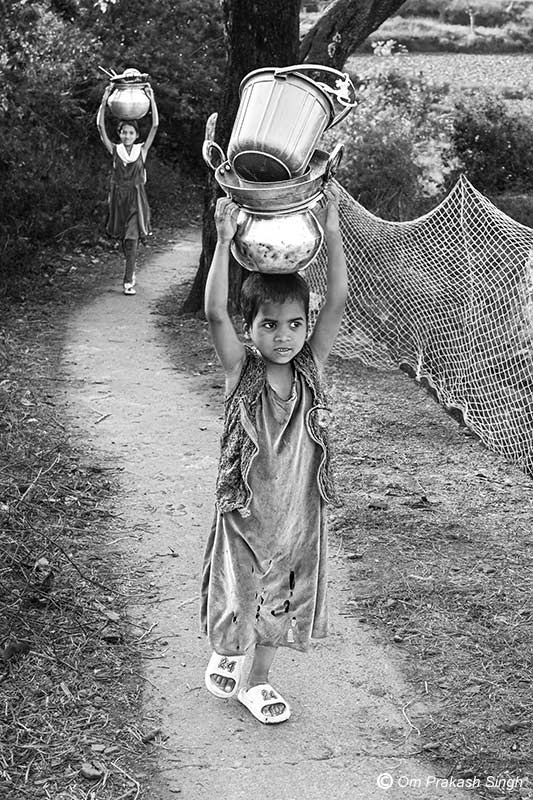

A very young girl child hauling water and clean utensils from a distant water source in Khunti district

Even very young girls are not spared from the burden of domestic water management. The photo shows a 7-year-old girl who regularly accompanies her elder sister to the Paata Daarhi closer to their hamlet. She helps by carrying home the cleaned utensils and drinking water in a smaller pot. The elder sister, seen in the background, hauls water in a larger pot.

Heading towards the village pond to wash clothes and bathe in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

Women in many households find the JJM water supply to be inadequate for washing clothes and bathing. According to their explanation, these activities require large amounts of water at the appropriate time. Many rural households in Jharkhand lack facilities for water storage in bulk, already noted earlier with regard to drinking water. Moreover, the JJM supply is time-restricted, mainly unavailable during the middle of the day when women have finished their household chores and are ready for washing and bathing. As a result, they often have no choice but to access ponds for this purpose, where water is easily available in bulk without much physical effort. Like spring-based drinking water sources, these ponds are also located far away, requiring a significant walk across uneven terrain and field bunds.

Washing the day’s clothes at a pond located on the village outskirts in Seraikela-Kharsawan district

This photo article has illustrated the various consequences faced by women and girls in villages where JJM schemes have been implemented, but the water supply through the FHTCs is either inadequate, irregular or qualitatively seen as unreliable. Also represented are the consequences faced in villages where implementation of JJM schemes is incomplete in coverage or delayed. What is obvious from this article (and the previous article illustrating the gaps in JJM implementation) is that mere installation of an FHTC at home does not guarantee the women and girls freedom from the drudgery of domestic water management. Only a ‘fully functional’ FHTC can help by facilitating them and other family members to undertake various water-related chores at home. If any one of the three functionality criteria of adequacy, regularity and quality remains unmet, then the purpose gets defeated. If there is a shortcoming on the ‘adequacy’ criterion, then water must be procured from outside or else the activity must be carried out at the external water source itself. The same holds true for the ‘regularity’ criterion, because irregular or untimely supply implies absence of water at home at the right time. Dissatisfaction regarding potability mainly concerns water usage for drinking and food preparation, and any lags here again imply water procurement from an alternate source that is seen as more reliable.

This photo article has elaborated how under different kinds of problem scenarios with JJM implementation and FHTC functionality, women and girls as domestic water managers face challenges. Manually carrying heavy water loads is not only an arduous task but is exhausting and poses serious health risks to women. The burden becomes even greater when multiple trips are required each day. Further, in the landscape of Jharkhand, which is geographically a part of the Chotanagpur Plateau, transporting water across uneven or hilly terrains is challenging. There is risk of slipping and falling with water loads, especially while accessing water from the distant spring-based traditional water sources located in the paddy fields. Extreme weather conditions, such as during the monsoon season, hot summer or cold winters, can further intensify these challenges. In addition, irregular or low-pressure water supply can cause spending longer unproductive times at the tap, further disrupting household routines and reducing productive hours. All this can make women to also compromise their income and overall socio-economic well-being. Further, girls often accompany mothers or even make independent trips carrying water. Very young girls too carry smaller containers of water. When children are forced to fetch water, they pay with their future. Carrying heavy water loads can cause neck and spinal injuries, and over time, this repeated strain may cause serious physical and growth-related problems. Further, hours spent fetching water mean hours lost from school, study, and play. Moreover, if the water supplied is not sufficiently treated (as per BIS:10500 standard) because of poor water quality monitoring and surveillance or due to inefficiently running water treatment plants, there can be illnesses such as diarrhea, or even physical conditions such as fluorosis. Diseases can potentially affect everyone in the family. These various hardships may ultimately limit women and their dependents from fully enjoying fundamental human rights, particularly the rights to water, health, education, and development.

JJM is undoubtedly a great tool to secure the human right to water for rural women and girls, and a harbinger of sustainable development in the villages of Jharkhand. The agencies responsible for implementation of the program need to be more sensitive to the hardships and challenges faced by the targeted beneficiaries as a result of inefficient, ineffective and delayed implementation of the program and adopt appropriate action to remedy the situation in the best possible way. For example, adequate and timely availability of funds must be ensured, and appropriate action be adopted to address the issues comprehensively. Engagement of the local beneficiary communities must also be effectively secured for the sustainability of the schemes. Comprehensive recommendations for enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of the JJM schemes will be proposed in a forthcoming article.